| Music Trade Review |

|

Die Zeitschrift Music Trade Review ist online verfügbar: |

|

Music Trade Review - Music

Industry Magazine

Online Library: 1880 - 1933, 1940-1954 The Music Trade Review was published out of New York from 1878 until at least 1956. It apparently suspended publication with the January 1933 issue. Publication was resumed under different management sometime between 1937 and 1940. Our online library contains issues from 1880 to 1933, and from 1940 to 1954. Additional years are available for review at a number of libraries. Search www.worldcat.org for more information about the holdings of other libraries, or ask your local librarian for assistance. |

| |

| --

google Anzeige -- |

| Bitte

teilen sie diese Seite: |

|

|

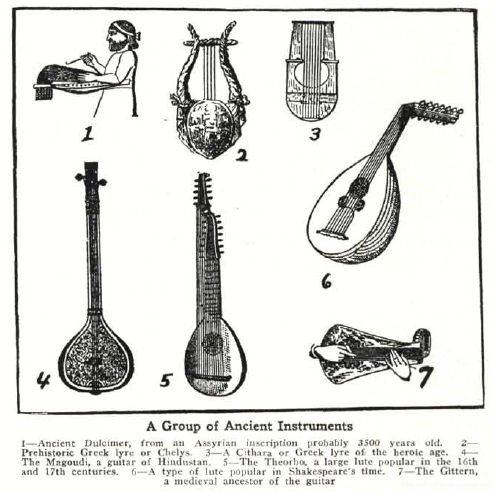

Fretted InstrumentsTHEIR ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT and MARKETINGFirst of a Series of Articles on Fretted InstrumentsBy LLOYD LOARThat large and ubiquitous family of musicmakers known as "fretted instruments," mandolins, guitars, ukuleles, banjos—has a nobler and more imposing history than the casual merchandiser or player of them might suspect. The very first stringed instruments that made their melodious sighings available to mankind so that there might be some point to springtimes, friendly gatherings, celebrations, inexpressible yearnings, and all that sort of thing, were the fathers of the fretted instrument families. It is true that no imaginative instrument maker had yet been able to conceive the idea of a fret to raise the pitch of a string and thus make one string serve for several notes. But the strings were plucked or struck, and the tone quality must have been greatly like that of their modern descendants. Such an instrument was the dulcimer of the Assyrians (cut No. 1) used 3,500 years ago, the prehistoric lyre or Chelys of the ancient Greeks (cut No. 2) used around 1000 B. C, the Cithara or more highly developed Grecian lyre (cut No. 3) in use from about 800 B. C. to the Roman Conquest 146 B. C. and the Egyptians of 3,000 years ago had instruments quite definitely lute-like in shape. So ancient are these instruments that nothing is known of their tuning and about all we do know of them is from the old inscriptions, as shown by these reproductions, handed down from those ancient times. From these remote times to the middle ages there was a gradual working out of more efficient models. Necks appeared, at first probably to furnish a more convenient means of holding, then this led to the accidental discovery of the possibilities of a change of pitch through stopping or shortening the string with the left hand fingers. From this came the idea of frets, and very crude the first ones were; pieces of cat-gut tied around the neck and passing over the fingerboard at somewhere near the proper intervals to produce a scale. Somewhere along the way they also acquired a well-defined body with a top or soundboard, and sides and a back enclosing an air body to amplify and give resonance to the soundboard tone. To trace these developments in detail would not profit us greatly, so it will suffice to say that by about the Fourteenth century there were certain general types evolving to fit the expanding demands of the musically inclined. Many sorts of lutes and guitar-like instruments were present in considerable abundance, and in certain sections South and East of the Mediterranean a combination of the plucked string and drum idea had long since given rise to a very primitive form of banjo-type instrument. By the Sixteenth century the definition of these instruments had become more complete. The Moorish influence via Spain, that of Arabia through the contact of the Crusades, the experimentation of unknown medieval artisans, and the interchange of ideas through the increased inter-communication between peoples, although usually from wars of conquest—all helped to bring it about. The lute family had attained a comparatively high degree of efficiency, and was represented by lutes of all sizes. Guitars, which were really a form of lute, were also of various sorts. A consideration of the various cuts shown, reproductions of old prints (cuts Nos. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) will give an idea of the variety of these instruments and their resemblance to modern ones. Lutes had all the way from eight pairs of strings to twenty-four. Some of the bass lutes only had one string, many of the most popular lutes had an extra short single string known as the chanterelle or melody string, like the fifth string of the five-string banjo. All sorts of tunings were used, some instruments were made with sympathetic strings and some with bass strings to the left of the fingerboard as in the case of the harp-guitar. Most lute music was written according to a system known as tablature. There was a staff-line for each string, a figure or letter on a certain line (as 1, 2, or a, b) indicated the first, second or some other fret for that string, a zero or open note the open string, and the time values were shown by a row of notes beneath the staff. From our standpoint these instruments must have been clumsy affairs. An early writer comments that "a lute player 80 years of age had probably spent about 60 years tuning his instrument," because they were so hard to tune. Thomas Mace in 1676 recommended that when not in use the lute should be kept in a warm bed and covered up to keep the moisture out of the glue joints, and also that a new soundboard a year was necessary because the string tension pulled them out of shape in that time. But in spite of that the lute family from the dawn of musical history to the appearance of the violin were the most important stringed instruments. Some of the first significant music to appear was written for lutes; favorite court musicians were lutists; Monteverdi, the father of grand opera, used various lutes in his orchestra, and so did Bach and many other great Seventeenth century writers. It was equally or even more popular with the average citizen, even barber shops provided lutes for their customers to strum their favorite ditties upon while waiting. This period of absolute supremacy for the lute family covered thousands of years; beside it the 250-year supremacy of the violin family seems short indeed. And it is not at all illogical to suppose that the elapse of still more time and the ingenuity of American artisans aided by the resourcefulness of American music merchants will again place these modern descendants of the lutes, known as fretted instruments, somewhere near the top of popular favor and musical effectiveness. The violin, blossoming forth from the multiple cocoon of the viol family, appeared. The harpsichord and then the piano accompanied it, and the lute family began to recede from public affection. About the beginning of the Eighteenth century the transition was completed, and the violin, harpsichord, and piano were monopolists of public favor, and the numerous members of the lute family were practically exiles. From a small lute known as the Mandura, by way of Spain and Italy came the first modern form of the mandolin, with four double strings tuned the same as the violin, and pear-shaped body with strips of bent wood for the back and sides, and a flat top or soundboard. The banjo appeared in America early in the Nineteenth century, having been brought by the Negro slave from his African home. The guitar, in its modern form usually credited to a German named Cetto about 1790, enjoyed a season of popularity about the time of the lute's decline, but this was brief and it soon retired to semiobscurity. In our own country guitars were manufactured successfully as early as 1833, the primitive banjo was gradually improved and attracted sporadic attention from shortly before Civil War times on, while the mandolin did not attract much attention until the '80's, its introduction being generally credited to Spanish students who demonstrated it very attractively. But until the beginning of the Twentieth Century there had been no real improvement in fretted instrument construction since the decline of the lute. Then things began to happen. The gradually growing interest in these fretted instruments stimulated manufacturers and dealers. The banjo acquired a sturdy, efficient, and artistic construction, tenor-banjos, mandolin, guitar, cello and ukulele banjos appeared; the violin construction was successfully applied to the mandolin, and tenor, baritone and bass mandolins completed the family quartet; the guitar was presented with a bigger tone, truer scale and more substantial build, and violin construction was in some cases satisfactorily applied to it. And the instruments began to engage the more active interest of the public. These improvements were solely the work of American artisans, and whatever advance you find in fretted instrument performance is indebted to American artistry and ingenuity for its existence. The list of those who contributed is long and noteworthy. Most of them are still in business: Bacon, Gibson, Martin, Paramount, Washburn, Vega—many more could be named. The instruments themselves offer advantages and conveniences, both musical and technical, so unique to themselves that it seems inevitable that the several seasons of fervent interest they have inspired, should continue and strengthen. Quelle / source: |

|

From left to right: First mandolin, Mando-Bass, Mandola (tenor), and Mando-Cello (baritone)Source: http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1929-88-28/79/ |

>>> Zurück zum Inhalt - Back to the Contents <<< |

| Wenn

sie diese Seite

ohne Navigationsleiste angezeigt bekommen, dann klicken sie hier um die MandoIsland Homepage zu öffen: |

|