| Music Trade Review |

|

Die Zeitschrift Music Trade Review ist online verfügbar: |

|

Music Trade Review - Music

Industry Magazine

Online Library: 1880 - 1933, 1940-1954 The Music Trade Review was published out of New York from 1878 until at least 1956. It apparently suspended publication with the January 1933 issue. Publication was resumed under different management sometime between 1937 and 1940. Our online library contains issues from 1880 to 1933, and from 1940 to 1954. Additional years are available for review at a number of libraries. Search www.worldcat.org for more information about the holdings of other libraries, or ask your local librarian for assistance. |

| |

| --

google Anzeige -- |

| Bitte

teilen sie diese Seite: |

|

Peggy Eames |

Fretted InstrumentsTHEIR ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT and MARKETINGFifth and last of a Series of Articles on Fretted InstrumentsBy LLOYD LOARIn the last several years a considerable change has taken place in the attittude of merchants toward their customers. At one time the favorite motto was caveat emptor, let the buyer beware; and even with all the bewaring of which he was capable he was often badly stung. Then things improved to the extent that the merchant did feel it incumbent upon himself to see that his customer secured a fair value for his money—not a bargain perhaps, but after that was seen to and the customer's money secured, it was no business of the merchant's as to whether the customer had any good out of his purchase or not. But now there is a big difference. The highest type of merchant and the most successful sees to it that the customer not only gets all that the merchant can give him for his money—he keeps in touch with the customer after the sale is completed long enough to be sure that the customer is pleased with his purchase and is able to use it to the best advantage for the purpose for which it was bought. Automobiles, radios, machinery, ice-less refrigerators, practically everything that is or can be sold on the time-payment plan (although not necessarily so sold) has thrown in with it this modern characteristic of the highest type of business known as service, except musical instruments. I know that some musical instrument merchants consider that they do give service to their customers, and so they do; but I don't know of any who give complete service; and I do know that the ones who come nearest to a program of complete service are the ones that are the most successful. We will first have to decide what complete service to a musical instrument purchaser really is before we can intelligently say how close the music trades come to giving it. In the first place it must be realized that servicing a musical instrument is a different proposition from servicing an automobile or a radio set. That is one reason why the music merchant has not yet developed his service program to the extent that other merchants have; it is not necessarily because the music merchant is a poorer business man or has more restricted vision. He has a good deal more to see than the other fellow, if he is to get an accurate picture of what real service is and what it will do for him and for his customers. Then these other articles that are largely responsible for the idea of service in business are comparative newcomers to the marts of trade. Their merchants had no lengthy history of a certain way to do business but developed their product, merchandising plans, and traditions almost simultaneously. The music merchant cannot do this. His traditions and customs were handed to him from a long ways back in the history of commerce, and he will necessarily be more loath to change than the merchant who has nothing to change. Inertia can only exist when there is something to harbor it, and anything that is moving at a given speed is bound to have inertia that operates against an acceleration of that speed. The radio and automobile merchants' service consists of seeing that the product performs well enough for a long enough time to prove that the material and workmanship represented in the article are as good as they should be; and that the purchaser is able to operate the article well enough to give himself as much pleasure and usefulness as possible for the article to give him, and that he also knows how to take care of it so it will last him a reasonable length of time. If the music merchant has as complete a service program, he will not only make it right with the customer, if the instrument does not stand up as well as the customer was told it would, but he will follow up the customer by 'phone or letter and be sure that it is doing so, and he will in addition see that the customer learns to play the instrument as well as his physical and mental endowment will permit. It is true, of course, that some buyers of musical instruments are already able to play them, hut if a business is to prosper, it must have new customers, new converts to the usefulness and desirability of its merchandise, and lots of them. And all of these new converts will be unable to play their instrument just purchased. This idea of service holds good for all the instruments a music dealer sells, including the piano and the douhle-bass; and those dealers that realize it first and complete their service program accordingly are the ones that will be most prosperous. For service of this sort is not just desirable because it is a favor to the customer; it is the result of a realization that a sale is not an isolated transaction; that it has a definite effect on all the sales that follow it, and if it is completely successful it will increase the number of future sales and assist in making them completely successful also. And the sale of any musical instrument is not a success until the purchaser has learned to play it. We are discussing fretted instruments particularly in these articles, and their angle of this particular sort of servicing that should appeal to the dealer is that they require so much less of it in order to complete successfully the sale. The greater ease with which they can be learned, their peculiar adaptability to children and beginners, especially those of but average ability, has been covered in previous installments and needs no more than passing mention here. This idea, of course, indicates an arrangement of some sort with a competent teacher. Many music stores have this, but it can be carried farther and handled better than it often is. The store should see to it, if necessary, that the teacher is successful financially. A good commission should be paid on sales for which the teacher is partly responsible. All or part studio space and club rehearsal rooms could often be furnished gratis to advantage. If the teacher is incompetent the store should be the first to know it and remedy it before anyone else knows it. There should be no necessity for giving lessons free with instruments; unless the store charges too much for its merchandise it couldn't afford to do so anyhow, and there is no need for the dealer to lose money by this servicing. See that the teacher gets a fair price for his lessons, be square with him and see that he is with you. Whenever a customer buys an instrument, all the information about that customer that can be politely extracted should be gotten and filed away. If no teacher has been selected by the buyer, introduce him to the one the store recommends. Then call him up later on and if he isn't making good progress find out why and assist in correcting it. If it involves the teacher considerable tact may be necessary in handling it, but tact in all departments of business is necessary nowadays and there is no reason why it shouldn't be exercised as skilfully here. Get the customer to come in and play for you so you can see how he is progressing and so he will form the habit of dropping in—he is apt to be in the market again or to have a friend or acquaintance who will be. Then there are supplies and music to be bought. See that he knows how to take good care of his instrument, whether he actually does so or not; and the great majority of buyers will take proper cart because the new instrument is apt to be very precious to them. When the small goods manager finds in his files that several fretted instrument purchasers are in the same neighborhood, try to start a club or orchestra with these players as a nucleus, interest them in the idea and they will help find the rest of the players necessary and will help you sell them the instruments they need. This can be done through some organization to which they all or for the most part belong, or else it can be independent of it. Get in touch with all sorts of organizations that might be interested in a club, social, fraternal, business organization, etc. Choruses, glee clubs and various groups of that sort are especially good prospects. Fretted instruments go especially well with voices, it will not take them long to learn to play them, and they can use numbers where they play and sing at the same time—which they cannot do with other instruments. Then keep in touch with these clubs, see that they are successful and prosper. Directors and coaches can be furnished in the same way that instructors are. See that they have a chance to play in public often after they are ready to, arrange for them to broadcast if you can— fretted instruments sound particularly well over the radio; give them your store name or something of the sort, or plan in some other way so that you can get good publicity out of the concert or broadcast. Various groups of school children are excellent prospects for dubs; if the music supervisor understands the possibilities and knows that you are exploiting the children first for their own good and yours only incidentally he is apt to be for you. It all requires thought, careful planning, consistent application and patience, but it will pay large dividends in satisfaction, the standing of your store and future sales. Source: http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1930-89-6/57/ http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1930-89-6/63/ |

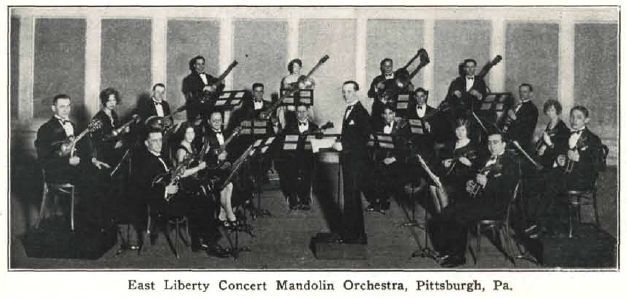

East Liberty Concert Mandolin Orchestra, Pittsburgh, Pa. |

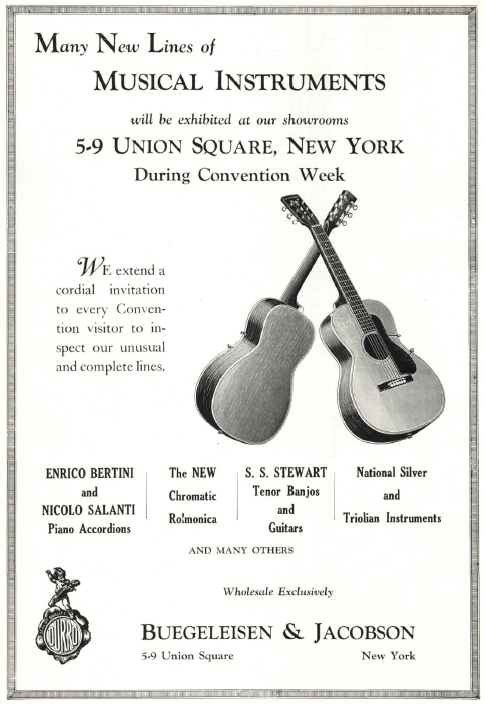

Buegeleisen & Jacobson - GuitarsSource: http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1930-89-6/57/ http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1930-89-6/58/ http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1930-89-6/61/ http://mtr.arcade-museum.com/MTR-1930-89-6/62/ |

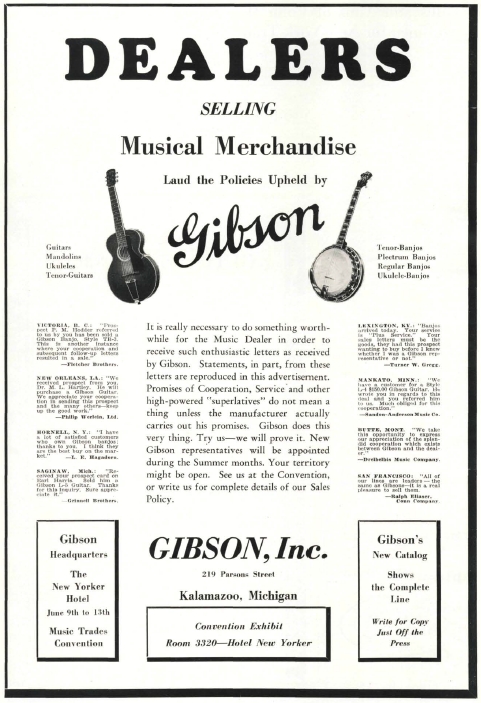

Gibson AD 1933 |

Globe Music Company - Special vacation Ukes |

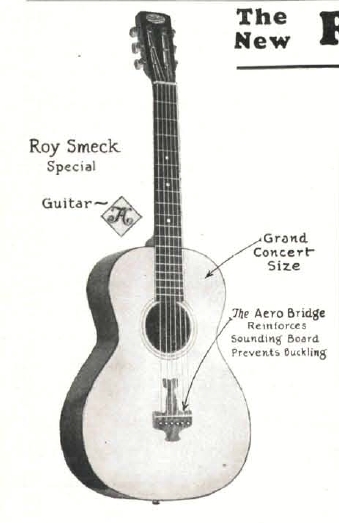

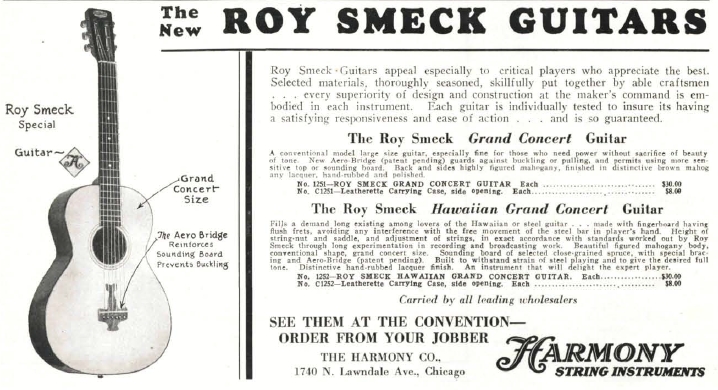

Roy Smeck Special Guitar The New Roy Smeck Guitars 1930 |

Vega Guitars - Banjos |

>>> Zurück zum Inhalt - Back to the Contents <<< |

| Wenn

sie diese Seite

ohne Navigationsleiste angezeigt bekommen, dann klicken sie hier um die MandoIsland Homepage zu öffen: |

|